Landscape art is almost never just a reproduction of a scene in a particular medium. Here in Rockland, Maine, the Farnsworth Art Museum (where I’ve had the privilege of teaching this year) is one of the keepers of Andrew Wyeth’s many landscapes, in front of which I have occasionally cried. It’s not just the Wyeth landscapes, either, that are so affecting. So much landscape art impacts me that way, especially if it’s focused on places I too hold sacred. I guess this is why I’m drawn to attempting it myself, so I’ll talk a little bit about some of the landscapes I’ve made using hooked fiber and why they matter to me. I hope you’ll think about your own landscapes, what resonates here for you, and how you might approach them differently too.

Perhaps a bit of a digression, but it’s no secret to my family and friends that I’ve recently become obsessed with Noah Kahan’s music. This young artist, born the same year as my youngest son, has positively nailed what it means to hold New England in your very DNA. His art medium is music, but the songs feel like landscapes to me, landscapes that are familiar and image filled, every word like a brushstroke or a hooked loop to convey the whole, sound choices working like color and texture. As an example, he’s brought the term “stick season” into the national vernacular, but those of us in New England can see and feel it as the music unfolds. “Stick Season” is a sonic landscape, as is “Northern Attitude,” “Maine,” and, really, most of his works.

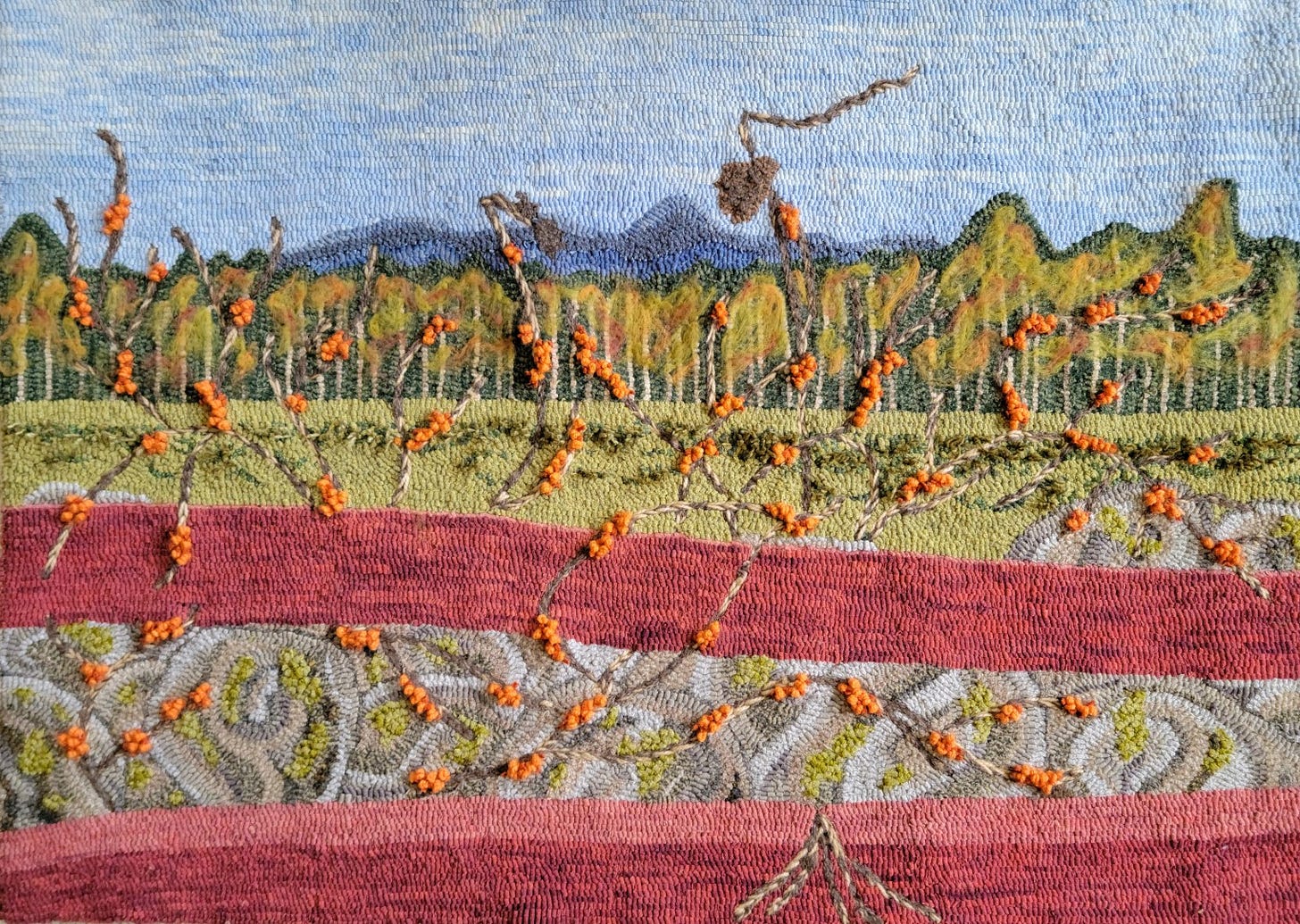

One of the first large landscapes I did, Bittersweet, was, in fact, a depiction of almost “stick season” here in Maine. I say almost because I am showing some foliage still left on the trees, mid-fall, as I look over my neighbor’s field in Paris, Maine toward the Mahoosuc and White Mountain range beyond. In the foreground is the ancient and falling stone wall with the weathered fence rails running askew, the bittersweet vines taking over (as they do).

This scene is different every single day. Honestly, it’s almost incomprehensible to the human mind that a single view can be different every.single.day, but this one is. Every sunset over this field is different and utterly spectacular, so much so that we regularly see cars parked along the road photographing it. I caught the scene at my favorite season here in New England and tried to lean in to the palette and textures of mid fall as it transitions into late fall, no more foliage but not yet snow, or the “season of the sticks.”

Landscapes don’t have to be strictly representational to be landscapes. When Making, then a print publication, asked me to do an article and hooked piece on the theme “Lines” in 2017, I created this, which is Maine Mountains (also in fall).

Lest you think I’m only inspired by fall, here is a winter example. I’ve had my Maine Winter Sunset exhibited and also on view at a few events and it always brings a lot of personal responses, including people wanting to touch it, which is a common with hooked art, I think. I rarely say “no” to that.

This piece came about after I stumbled out of my house in Paris one winter evening, just before dinnertime, to feed my chickens. The snow was pretty deep and I wasn’t looking forward to trudging through it to the back of the barn, but I was stopped in my tracks when I saw the fiery sunset, which, I swear to you, looked pretty much as it looks on the finished art piece. It was reflected on the smooth snow and the treeline was near black in front of it. When I look at this piece now, I am taken back to the cold on my face, the sound of the snow caving in under my feet, and an overwhelming awareness that life meant more than the livestock chores I was rushing through or my resistance to going out. Maine does that to you. If you’re for a moment wrapped up in the mundane and feeling as though that’s all there is, this environment is always ready to shake you loose from that. Landscape art is a way of freezing that moment in time and going back to it over and over, not only while the art is being created, but long after it’s finished. If the art moves on to another human and they overlay their own meaning onto it, so much the better.

Last month I was on our annual Get Hooked at Sea adventure aboard the Schooner J. & E. Riggin with my colleague, Ellen Marshall (Two Cats & Dog Hooking). Together we comprise 207 Creatives. Each year for this event we hire an outside teacher and this time we had artist Diane Learmonth, of Stockton Springs, Maine. One of the projects she so capably led us through was creating an 8” x 8” mini-landscape. Toward the end of the trip, as is true so often on this excursion, there were tears. As the students showed their work and explained what it meant to them, several cried - with joy, with remembrance, with accomplishment, with overwhelming emotion. Their landscapes weren’t just static images of what they’d seen on board or perhaps remembered with the help of their photo files. Their landscapes were stories. As human beings we are wired for storytelling. We do it through conversation, through music, through journaling and writing, and through visual art. Fiber lends itself to a tactile, textural telling of the story, something we can run our hands over and feel in three dimensions. It’s a somatic, integrated experience.

This was my project on board, a depiction of Harrington Cove at Spruce Head, Maine. Had it been finished at the time of our disembarking, I might have been one of the criers too. A dear friend of mine, artist Charles Wilder Oakes, passed away a year ago this week. He was an artist and philosopher and someone I looked up to in about a thousand ways. The last words we had with one another were “I love you,” which I regard as the best parting words we have available to us. He was actively dying of cancer and I still keep his last phone message in my voicemail. It’s hard to think I’ll never hear his voice again any other way. His art was recently exhibited in a retrospective at the Blue Raven Gallery in Rockland, because isn’t it always after an artist is gone that their work gets the most comprehensive notice? Blue Raven handled the exhibit with profound sensitivity and respect and I think everyone who knew Wilder is grateful for that.

Harrington Cove was a favorite spot for Wilder. He posted many, many photos of it on his social media, it being on his almost daily stroll near his own home and studio (the “house that art built” he told us) on nearby Cline Road. Those of us who watched his page knew we’d be treated to Harrington Cove photos of all tides, all seasons, all times of day. He simply loved the spot and also incorporated it into his art. For me, making the mini-landscape of Harrington Cove was a meditation on my gratitude for this long friendship and a working through of still very fresh grief.

Finally, I think it’s safe to say that we don’t have to be too precious about our landscape art. These block-mounted smalls are not of specific places, although they bring to my mind and heart the sea under a winter sky and the baling of hay in late summer, toward fall here in Maine.

These are made relatively quickly (relatively being the operative word in such a slow process art) and often with the leftover stash I have from a larger project. They are meant to capture a memory or feeling without a specific story, which I think makes them very accessible for someone else to own and attach their own story to.

I don’t think I’ll ever stop making landscapes, even though I work in other subject matter too. For me they are a direct line to something so much bigger than I am, a connection to the Earth and environment from which we should not be separated. The stories of our lives are written on and by the landscapes surrounding us. No one’s life is separate from their environment and if we’re paying attention, we can work with that reality to bring a sense of larger context to our existence.